If you saw the recent documentary by Ken Burns and Lynn Novick about Ernest Hemingway, the filmmakers were tasked with condensing one larger-than-life man into a mere six hours of screen time, an impossible task. Faced with tough choices of what to leave in or out, they overlooked an important place, Wyoming, and an influential person, Ernest’s second wife, Pauline Pfeiffer.

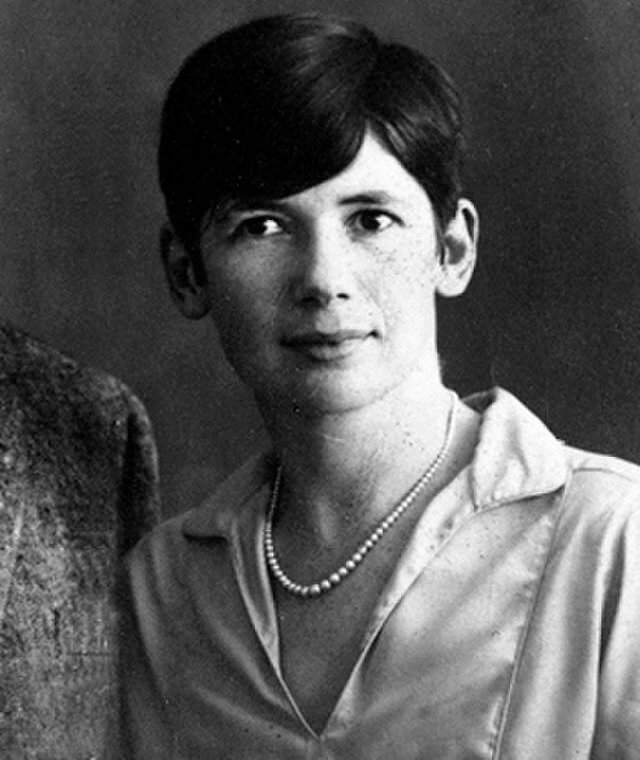

In scant airtime, both Pauline and Wyoming were mentioned, but filmmakers skimmed over the significance of both in Hemingway’s life and success. Many books have been written about Ernest Hemingway’s relationship with Hadley Richardson (wife number one) and Martha Gellhorn (wife number three), but few have covered his time with Pauline Pfeiffer, wife number two. A former Vogue editor in Paris, she edited all his work from 1926 to 1939, arguably the most prolific period of his career and the years when he became known as one of the greatest writers of his time. Labeled the “other woman” and blamed for breaking up Hemingway’s marriage to her friend Hadley Richardson, Pauline has been nearly erased in the story of Hemingway’s success. Yet she was one of the only editors he trusted and when he left her for Martha Gellhorn, he asked his editor Maxwell Perkins if Max thought Pauline might still consider editing his next book, For Whom the Bell Tolls. (The answer was no!)

Ernest Hemingway saw Pilot and Index Peaks from his Wyoming cabin (photo: “Bear Tooth” by kern.justin is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0).

Wyoming also played a key role in Hemingway’s writing. He spent six summers there, finishing the draft of A Farewell to Arms during his first trip West in 1928, and working on numerous books during subsequent visits in 1930, 1932, 1936, 1938 and 1939. Although he wrote the short story “Wine for Wyoming” based on his experience during his first visit to Sheridan, Wyoming, he kept his Wyoming time on reserve in his head to write about in the future, when he felt he could do it justice. Shortly before his suicide in 1961, he mentioned to his friend Bill Horne how he longed to repeat their time together in Wyoming, a place that he described to his friends as “cockeyed wonderful country.”